There's a Pass For That

It feels like just yesterday that the subscription box craze had gone peak mainstream – and now boasts hundreds of options across of dozens of categories. The mania was principally driven by two factors: extremely low barriers of entry to reach even material volumes of customers ($250k GMV+) and dozens upon dozens of niche audiences to cheaply target via social media. The consequence of those factors? Largely unsurprising: a couple of category killers in the biggest verticals as well as hundreds of smallish, mostly stagnant, (hopefully profitable!) niche digital small businesses.

Years later, in hindsight, the predictive factors for a winning subscription commerce model are abundantly clear – (1) a consumables category in order to reduce churn, (2) a strong content/influencer platform to enable low cost scalable acquisition channels, and (3) a clear path towards manufacturing vertically integrated products to enhance margins. The emerging leaders – Dollar Shave Club, Ipsy, and Honest Company all perform well across each of these three factors.

Nobody Puts Classpass in the Corner

Like Groupon, Uber, and Birchbox before it which spurred innumerable similar models, the ascendency of Classpass has, over the past 12 months, lit a fire to become the next Classpass for X:

Kids: Pearachute/Littlekey/Kidpass/The Kid Passport [Disclaimer: Chicago Ventures is an investor in Pearachute]

Beauty: Vive/Beautypass

Sports: Forelinx

And yet again, consumers are met head on with the next generation of subscription models. Only this time, rather than packaging physical goods into subscription models, the new emerging class of companies are packaging experiences into monthly subscriptions.

The question entrepreneurs, investors and consumers need to ask is: are things any different this time around? Is the model fundamentally sound? And though subscriptions may feel like an over-hyped tech buzzword, the reality is that fundamental products in our lives all revolve around de facto subscription models: smartphone plans, rent/mortgages, and insurance.

Learning From the Passt:

One of the unfortunate realities of the subscription box craze is that it often ignored the imperative of providing a win-win on both sides of a transaction – to both consumers and merchants. Case in point: many independent manufacturers and brands would provide free product or samples to the box companies at the outset when their subscriber bases were 5-10,000. This was a win-win; the curating companies got product for free (win!) and the manufacturers got low cost (at cost) exposure and endorsement to a highly targeted, pre-qualified audience of subscribers.

It was a good deal at 10,000 subscribers for the manufacturers. But it was an expensive, often unprofitable proposition to provide free or at cost product to 100,000 subscribers, many of whom were less ideally qualified targets as the quality of subscriber began to degrade. What started as a win-win scenario, became extremely lopsided – and ultimately unsustainable.

Sarah Tavel, a partner at Greylock, in her fantastic piece “Taking the Wrong Lesson From Uber,” commented:

“Yes, convenience is huge, but it was only part of the picture. The magic of Uber is that it used mobile to create a 10x better product than the incumbent (taxis), and did so at a lower price. The “and” is everything.

Which brings me back to the “on demand economy”. The challenge I see with so many of these services is that most often, 1) they are new costs, and 2) they don’t fundamentally recast cost structures like Uber did — instead, many of them are an arbitrage on the cost of wealthy people’s time vs the less wealthy.”

Sarah’s comment isn’t solely applicable to on-demand companies – it’s accurate for any re-imagination of a consumer process. Thus, based on her logic, it follows that the question for the new generation of companies aggregating and productizing experiences is: can it solve a fundamental pain point for consumers (10x better product) AND provide a discount to their normal course of action? I would suggest one additional variable: can it provide incremental value to the other side of the market – “fundamentally recast[ing the] cost structure” in favor of the merchant – rather than cannibalizing existing revenues?

Passanomics:

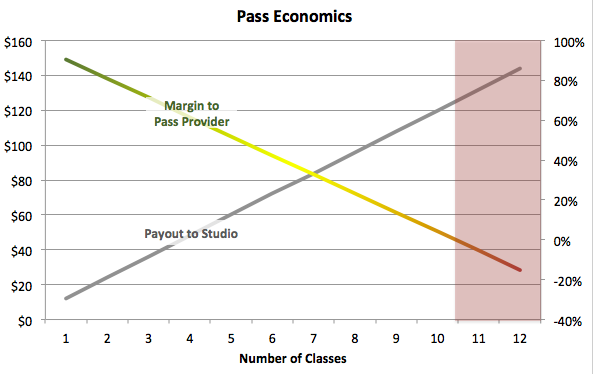

First things first – is the model sustainable? Though each of the companies identified above has nuances of its business model, Classpass is the paradigm. Here’s an estimation of how an average month looks like for the company:

In New York City, its most mature market, Classpass charges $125/mo and remits to studios approximately $12/class. It’s actually an extraordinarily powerful model: Classpass breaks even, even if a customer were to take 10 classes in a single month. And most importantly, with a perceived value of $25-40/class, Classpass is of value to the end consumer at 3-5 classes/mo, a 40-60% gross margin endeavor.

But wait, there’s more! Compare the subscription pass model to your traditional transactional marketplace:

By contrast, in order to generate a comparable revenue margin as the subscription model, a traditional marketplace model would need to generate between 8-13 unique purchases. Per month. Month over month. That’s practically unprecedented across any digital marketplace in history. And it’s these challenging economics that are likely the reason why hyper local marketplaces such as Sosh have historically been so difficult to scale. Consider further advantages:

Avoids the re-engagement expenses required to generate all transactions past the first.

Healthy first month margin to get aggressive on customer acquisition cost.

Many creative ways to minimize churn either via waitlists, grandfathering in cheaper rates, or no-cost pauses of service.

All in all, from an operational perspective, the subscription model yields considerable leverage in generating outsized revenues on a similar cost basis – meaning, that whether one operates a transactional model or subscription model, they still incur similar costs in sourcing, vetting, and onboarding their supply side inventory. It’s just a far more profitable way to monetize the supply side.

That Counterintuitive Thing About Pass Models

Ultimately though, the intrinsic struggle of the Classpass model is that the arbitrage between a consumer’s perceived benefit of the service and the fees remitted to the provider is actually so extreme, that companies may show seemingly credible signs of early product/market fit that actually mask its underlying business model issues.

For example, while Classpass has undeniably gained significant consumer adoption, it’s still very much iterating on its own processes and product. From an April 2015 New York Times piece on the company:

The service, now in 33 cities including Los Angeles and London, has democratized boutique fitness and has rabid fans among those with flexible schedules and a willingness to try new studios. [But] as fitness companies attract an influx of new students, studio regulars, who often pay upward of $30 a class or more, are contending with larger crowds, less physically intensive classes and etiquette offenses like excess chatter and too-long showers. Many ClassPass members say it has grown difficult to get into the desired classes.

Studio owners are struggling with ambivalence too. Lauren Imparato, the owner of I.Am.You, a yoga studio on Mulberry Street in Manhattan, accepts ClassPass students but sometimes worries that participation has a negative impact on the serious practitioners in her classes, and told her instructors to keep up the pace… Some are worried about the perception of offering deep discounts.

To be fair, representative growing pains would be reflected at nearly any early stage startup. Nevertheless, the struggles – both amongst consumers and merchants – suggest that while the model may be “recast[ing]” a cost structure to the consumer’s benefit, it isn’t necessarily addressing a deeply painful problem or brokenness within the industry itself. And it’s fundamentally impossible to build a 10x better product unless that product is addressing an inherent breakage in existing process. On the other hand, you could argue that macro trends in the way people take fitness classes - on short notice, geographically necessitated - create the perfect storm of macro needs for a product such as Classpass to exist.

How Classpass itself will ultimately fare and iterate remains to be seen – and they’ve certainly come along way in ensuring success on both sides of their market. When productizing experiences, ultimately the merchant – not discounts – are the star of the platform. And in order for any “pass” to succeed and thrive, it must address both an existential pain for the merchant while providing an enhanced value and convenience for the consumer. Anything less is unlikely to predictive of success.